I always found a fascination with electronics, having helped my father assemble and troubleshoot a number of Heathkit projects at a very early age. It was a natural progression to dive head‑first into the fascinating world of computers when they hit the market big time in the 70s & 80s.

This was also the era when arcade halls started sprouting left and right, and many a teenager’s days were dedicated to spending quarters and trying to beat their friends’ high scores.

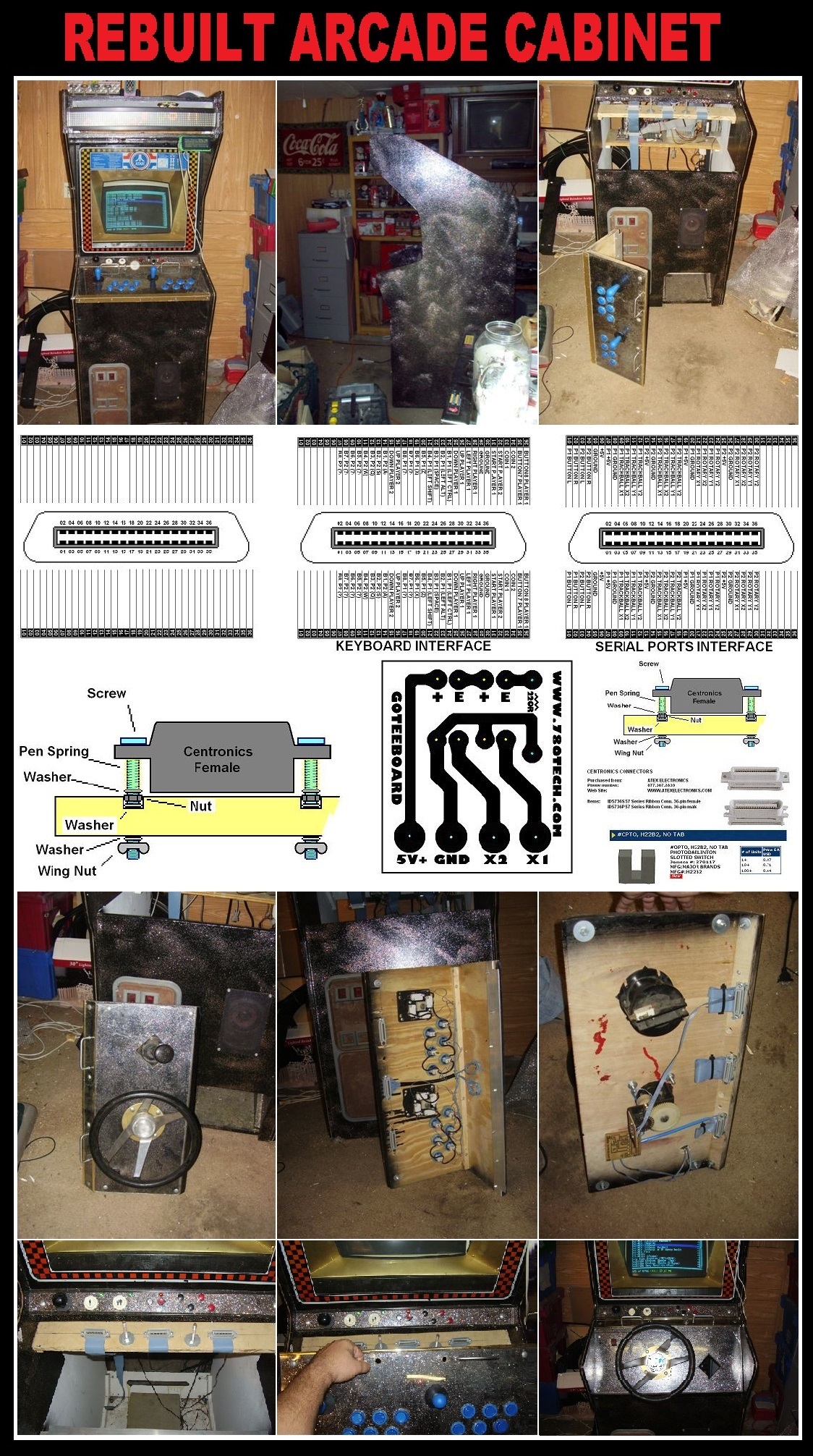

Fast forward 20 years. A friend offered, for $100, a beaten‑up, water‑damaged, non‑functional Pole Position cabinet. I jumped at the opportunity.

Many months were spent carefully disassembling this beast. Each piece was removed and used as a mold to trace and cut new parts from marine‑grade plywood to bring the cabinet back to life.

Very special thanks go out to my dear friend David Rareigh, who graciously purchased and donated the plywood for this project — and then spent years afterward entertaining and helping with every wild idea I came up with.

To make this a full‑blown multicade machine, I needed exchangeable controls so I could use a standard joystick layout or the original race‑car steering wheel, gear shifter, and pedals. I designed a plug‑in system based on Centronics connectors locked in place and mounted on springs so they could wiggle and form‑fit to whatever control panel was being plugged in.

I opted for three plugs on each control panel:

- One for keyboard inputs (attached to an IPAC module) which plugged directly into a DIN‑5 keyboard connector (later a PS/2 keyboard connector).

- One for the driving wheel (or trackball), attached to a custom circuit I designed and etched based on a computer mouse, which connected to a serial mouse port (later PS/2).

- One reserved for future possibilities.

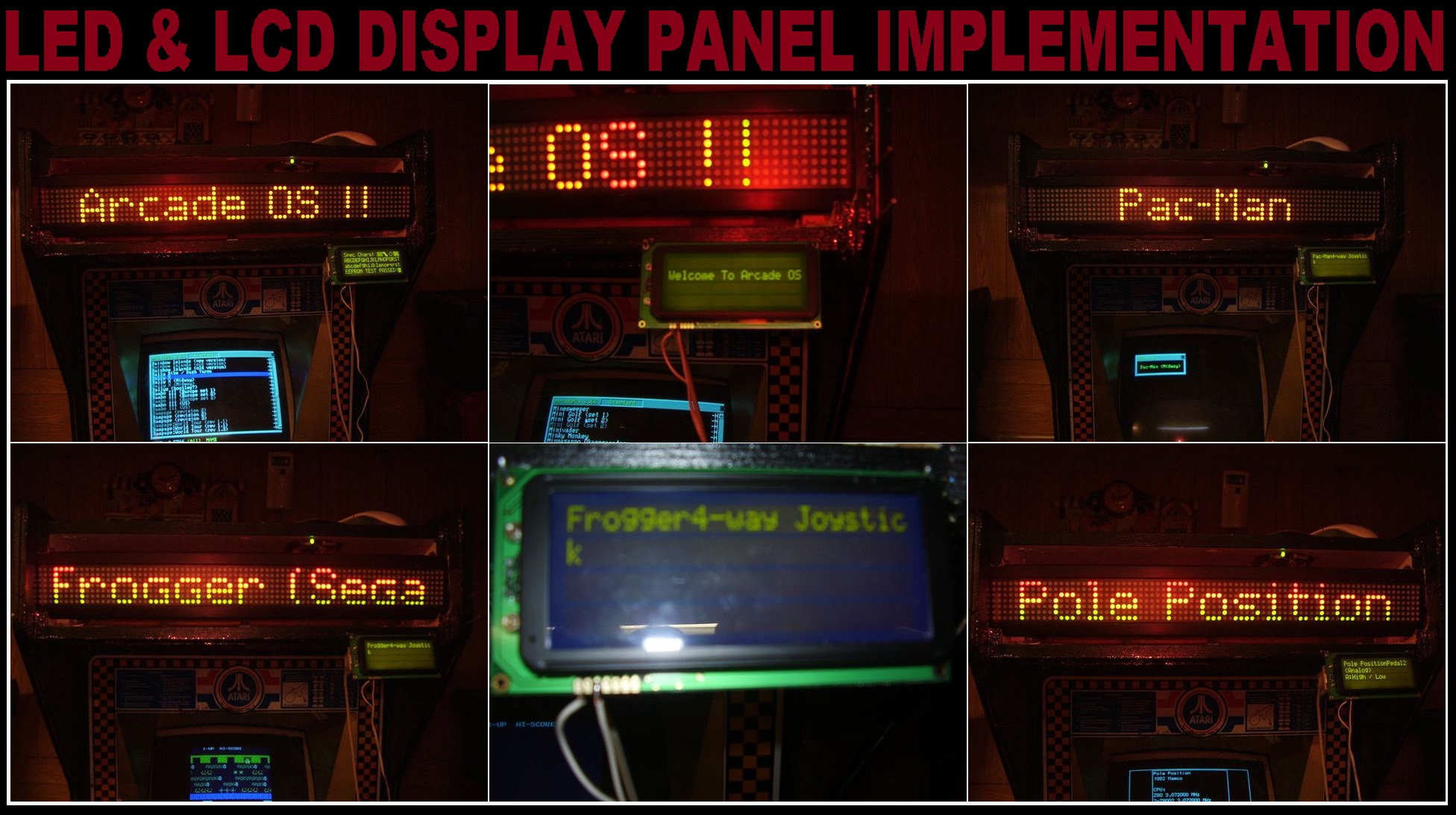

The final touch came when I envisioned the machine sending messages to an RGB matrix displaying information about the current game being played. I purchased a “relatively inexpensive” Betabrite sign on eBay and learned how it worked. The computer would send data to the sign through a serial port, which I captured and analyzed until I had basic code successfully relaying messages.

Although I had done extensive research on arcade machine emulators such as MAME, I lacked the expertise to implement this myself. I realized that MAME generated databases with information about which controllers each game used and which buttons were assigned. I wondered: How cool would it be to relay this info to the player before each game started?

Using the main RGB LED matrix for both name and instructions would be messy, so I considered a secondary display: a small LCD capable of providing supplemental information to the player.

At the time, there were many inexpensive serial‑driven interfaces on the market. If I could send information through one serial port, it wouldn’t be much more work to send additional information through a second serial port, so I purchased one of these as well.

For the emulator frontend, I discovered a highly configurable option called ArcadeOS. While it wasn’t under active development, I found that Carlos Santillan had done a couple of recent updates. After a quick search, I reached out.

Mr. Santillan was open to the ideas and spent a great amount of time discussing the project. After hunting down more parts online and sending them to him, we were on our way — several weeks of back‑and‑forth code and testing later, we had a working prototype.

To this date, and to the best of my knowledge, his machine and mine were the only two arcade machine prototypes capable of sending game and gameplay information to two separate displays simultaneously.